by Rosemary Keevil

Grief is physical.

Grief grabs you and keeps you in its clutches.

Grief comes at you and punches you in the stomach.

And just like those punches, the initial jab being the most powerful. Then it wavers a bit in its intensity, grief in the long term softens with time. But it never goes away entirely. It sits in you at a cellular level and seeps to the surface unannounced, often at significant anniversaries such as date of death, birthdays, and, in my case, the last healthy date.

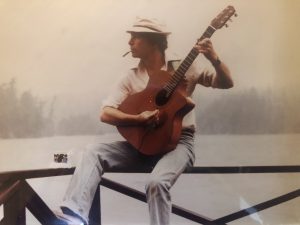

The last healthy date arises for me on January 9, 1991. It was a Paul Simon concert at the Pacific Coliseum in Vancouver, British Columbia. It was a cold winter evening, the city still recovering from a snowstorm. My husband, Barry, and I were early for the concert to buy tickets from scalpers, which we did with time to spare. We decided to walk a few blocks away to find a place for dinner.

Barry’s right knee was hurting him as we maneuvered along the icy sidewalk, which had not been cleared since the recent storm.

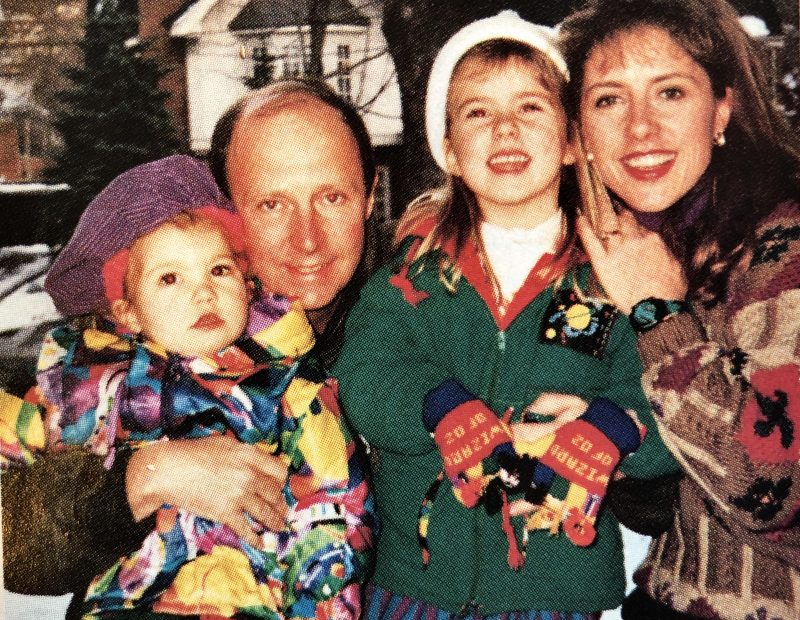

That was the first sign. Within a month, Barry was diagnosed with very aggressive and terminal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Without chemotherapy, he would be dead in six weeks; with chemo under a year. He was 41 years old; I was 36. Our daughters were two and four.

Two weeks before Barry’s fatal prognosis, there was another deadly prognosis in my life. My brother, also 41, was diagnosed with AIDS. In those days, an AIDS diagnosis was fatal.

I was obviously responsible for Barry’s medical care, but I was also responsible for my brother’s medical care as I was his only relative in Vancouver. The rest of our family lived in Toronto.

I had been living an idyllic life; a dearly loved wife and a proud mom with a promising career in the media. Suddenly, I was consumed by a fury of demands of two dying men, as well as two confused and needy little children. Doctors’ visits; hospital visits; CAT scans; MRI’s; blood tests; more medical tests; IV drugs; chemotherapy; surgeries; emergencies; my brother’s suicide attempt; trying to get and keep childcare; and the volatile moods of the kids, Barry and Rob.

One doctor aptly described it: I was in “crisis mode.” I was merely surviving. I did manage to exercise regularly; jogging and swimming and started relying too much on chilled, buttery Chardonnay. The seeds of alcoholism and addiction were planted. They did not sprout for another five years.

Barry survived until September, and Rob – poor, dear Rob. I had precious little left to give him after Barry died – survived another six months.

During that time, I bought so many books about death and grieving that the check-out lady at the bookstore asked if I worked on the palliative care unit.

I had to understand how to help my daughters and myself grieve. I learned that children grieve in different ways depending on their age. Dixie, who was three, wouldn’t have a concept of the finality of death. One day, when we were at the grocery store in front of the canned beans, she looked up to a stranger standing beside us and said, “It’s my birthday and my daddy’s dead, dead, dead.” I felt sorry for the woman.

Whereas, Willow, who was five, asked me who to tell that her father died. I explained that she could tell teachers, caregivers, friends’ parents but that she should explain that her daddy was fine last Christmas, then got cancer and died in September.

In fact, talking about their deceased father is part of what they needed to do. Children need an outlet for their feelings, so encouraging them to talk, draw and write is vital. Traditions and daily routines are crucial too, but it is equally important not to push them into these activities.

Also, the books informed me about “maladaptive behaviour.” Oh my, the girls really acted up. They had tantrums, were constantly fighting with each other, saying “I hate you” to caregivers, clingy and were genuinely naughty. But what could a mother do?

I learned that what I needed to do was to let myself grieve as well. I needed to accept that the only way past paralyzing grief is through it. Grief is exhausting. It requires hard work. I needed to sleep, to let myself be sad, have breakdowns, and give myself time. The death of a loved one creates a gash in the soul that will never go away entirely, but the ragged edges of the cut will soften with time, and for me, with professional therapy.

After Barry and Rob died, I held it together somewhat until 1996; and then fell into the grips of alcohol and drugs. I was a “high-functioning alcoholic and drug addict,” which is a bit of a misnomer as all it really means is that I was able to go to work. But I crossed many lines in the sand (and snorted many lines of cocaine), such as driving the kids drunk and stoned, driving their friends drunk and stoned and, unfortunately, I could go on.

I did go into rehab on May 3, 2002, and have been clean and sober ever since.

I learned that, as with grief, the only way past addiction is through it. To understand why I was numbing myself, my own grief and the stress of single parenting two grieving little girls. I needed to accept what I had done. To accept the shame and guilt, and also deal with any unresolved issues.

I found the 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous quite powerful. I know AA is not for everyone, but some elements do work, such as the necessity of cleaning up the wreckage of the past, facing your demons, dealing with resentments and making amends to people you have harmed.

Again, the only way past it is through it.

What happens next is what matters. And that is to try to do the next, right thing. I am still a work in progress. As I write in the last paragraph of my memoir, The Art of Losing It: A Memoir of Grief and Addiction:

“I know I cannot change the past. I know I will never lose the sadness over the death of my husband and the death of my brother. I will never lose the guilt I have over how I parented the girls in the absence of their dad, but I have acceptance. It is what I am doing about it now that matters today.”

For more information on Rosemary Keevil, check out her website.

Support us by driving awareness!

Subscribe to our YouTube channel at YouTube.com/GrapGrief.

Follow us on Facebook at Facebook.com/GrapGrief and on Instagram at Instagram.com/GrapGrief.