By Jean Brunson

For 279 days, grief has become a constant in my everyday life — a space where I was once familiar but not to this magnitude. My very first experience with grief was losing my grandmother at the age of 14. The matriarch of the family I’d have the honor of caring for until her last day on earth. Growing up in a Samoan household, funerals were standard and highly viewed as a way to honor your dead. It is an unspoken rule that everyone must say their goodbyes when they lose a family member. This rule applies from the eldest to the very youngest of the family tree. As such, death and grief were conventional within my upbringing, but as I reflect-it was not truly understood by my 14-year-old self.

Our entire family gathered at the hospital the day my grandmother passed to say our goodbyes, pray with her and sing traditional Samoan songs. I remember feeling immense sadness and loss when I think back to this day of sorrow. I can vividly remember the cries and wails that escaped the bodies of my grandmother’s children: my aunts, uncles, and my mother. I witnessed their pain and shared cries with them, and 23 years later, I am starting to understand the depths of their agony.

Our entire family gathered at the hospital the day my grandmother passed to say our goodbyes, pray with her and sing traditional Samoan songs. I remember feeling immense sadness and loss when I think back to this day of sorrow. I can vividly remember the cries and wails that escaped the bodies of my grandmother’s children: my aunts, uncles, and my mother. I witnessed their pain and shared cries with them, and 23 years later, I am starting to understand the depths of their agony.

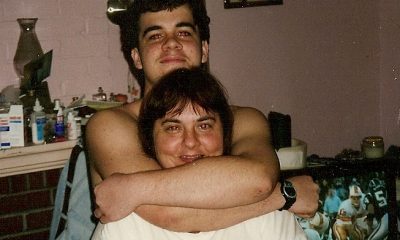

On November 17, 2022, Sofia, my mother, died suddenly. Truthfully, a piece of me died that day as well. Nothing can mentally or physically prepare you for a catastrophic loss like this. My mother lived with me and helped care for my children; she was a massive part of my everyday life. We’d share the day over dinner every night. I was creating a family tradition that we all looked forward to daily.

The day before, November 16, I rushed home from work following a phone call from my husband. He exclaimed, massive concern as he found my mother dazed and experiencing shortness of breath. When I arrived at my house and saw firsthand my mother’s condition, I had this gut feeling that she was slipping away. I’ve never in all my years of life seen my mother’s eyes so empty and her health at a rapid decline. I called the ambulance, and the operator remained with me until the EMTs arrived.

With the rise and fall of my mother’s chest, her breathing became increasingly shallow with every passing second. I tried my best to keep her comfortable but was unsuccessful; she, too, could not find a sitting position that allowed her lungs to expand and take a deep breath. With the EMTs finally on the scene, my mother was quickly swept into the ambulance. At the hospital, my sister and I were called back to the ICU to meet with the doctors. At this moment, I remained hopeful but had encountered this type of scene in the past; this day reminded me of my 14-year-old self, who witnessed my grandmother’s death.

With the rise and fall of my mother’s chest, her breathing became increasingly shallow with every passing second. I tried my best to keep her comfortable but was unsuccessful; she, too, could not find a sitting position that allowed her lungs to expand and take a deep breath. With the EMTs finally on the scene, my mother was quickly swept into the ambulance. At the hospital, my sister and I were called back to the ICU to meet with the doctors. At this moment, I remained hopeful but had encountered this type of scene in the past; this day reminded me of my 14-year-old self, who witnessed my grandmother’s death.

For the next 12 hours, my sister and I sat at my mother’s bedside, sharing tears, silence, and periodically FaceTiming with our other two siblings who were frantically searching for flights as they raced against time to share one last moment with our mother. My sister and I held our mothers’ hands but also looked on as doctors and nurses rendered aid to save my mother’s life.

My mother did not make it despite the endless efforts that the fantastic staff provided. The cries and wails that my aunts, uncles, and mother shared 23 years ago came rushing into my lungs with full force. Feeling the warmth leave my mother’s body has been a lasting imprint. The pain and the depths of this type of sorrow were unimaginable until November 17, 2022.

These past months have been confusing and complicated in my life. Suppose I’m being honest: one of the most challenging times ever where I was not able to just “get back up on the horse.” I’ve brought life into this world un-medicated, and I’d prefer the pain of childbirth over grief, any day. Grief lingers; it has a mind of its own, and it will find a way to force you to pay attention to its presence one way or the other, whether it be at work, a wedding, driving, a birthday party, or simply grabbing coffee. When it strikes, you must be intentional with giving grief the attention it requires to operate in the day-to-day tasks.

Consequently, grief has pushed me to blog about my experience. Whether it be through my social media platforms, recording voice messages, or journaling. I started discovering that I had to get my thoughts out of my system as I was experiencing large amounts of anxiety, stress, depression, and overwhelmed feelings. Until I became a part of the grief community, there were so many things I was not aware of: friends and family going silent, the slowing down of calls, others feeling uncomfortable about death, platitudes, the misunderstanding of what grief is, or how much time one should grieve.

Consequently, grief has pushed me to blog about my experience. Whether it be through my social media platforms, recording voice messages, or journaling. I started discovering that I had to get my thoughts out of my system as I was experiencing large amounts of anxiety, stress, depression, and overwhelmed feelings. Until I became a part of the grief community, there were so many things I was not aware of: friends and family going silent, the slowing down of calls, others feeling uncomfortable about death, platitudes, the misunderstanding of what grief is, or how much time one should grieve.

Within this grief space, I’ve been able to discuss the taboos of death and make a very uncomfortable topic feel more common. It’s allowed me to express to others that they’re not alone in their grief. I am able to utilize this platform as a way to educate that grief doesn’t always look “this” way. I like to offer a raw perspective with hopes that 1) the audience feels seen in their pain and 2) a person who’s not experienced a significant loss can become curious about someone else’s experience.

Grief is raw and unfiltered; those of us in this forever club recognize it in one another. I agree with the many grievers out there, grief is exhausting and ongoing. It’s a whole-body experience and can create large amounts of fatigue and concentration difficulties. I hope someone reading this will know, they’re not alone, and there are so many of us out there that are still trying to make sense of this experience. What I can also share is I understand my mother’s pain so clearly now. I don’t like that it took for her to die for me to fully understand her years of carrying lifelong grief and pain. As the youngest child, she’s watched those who’ve come before her die one after the other, starting with her father (my grandfather).

It should be noted that grief discoveries will become second nature in your daily living; I am wrestling with this myself as well. I’ve realized that emotions are complex. One moment, you’re smiling, and the next, you’re crying and longing for your loved one. In my case, longing for my mother has been a phenomenon that I’ve not entirely come to terms with. On the one hand, I know she’s never coming back, but on the other hand, I keep hoping to see her in the house folding her laundry or getting a phone call from her during the middle of the day just to say “I love you.” It’s this feeling of hope that continues to grow, and I’m hopeful to be reunited with her in another lifetime. My love for her continues to increase, and I’d live a million lifetimes if it meant I’d be reunited with her once more: to feel her embrace, share a laugh, or hold her hand.

As a result of my grief, in my work as a therapist, I continue to help others find language and make space for their own grief experience. Helping has always been a part of my DNA. I am honored to speak forward about grief and shed light on an experience or topic that we all will inevitably be faced with. Grief has offered me a perspective that I never had before. In essence, I suppose I can only attribute this to one person: my mother, Sofia Sakaria.

Ou te alofa tele ia te oe, mommy (I love you so much, mommy).

For more information about Jean, you can check out her website.

Support us by driving awareness!

Subscribe to our YouTube channel at YouTube.com/GrapGrief.

Follow us on Facebook at Facebook.com/GrapGrief and on Instagram at Instagram.com/GrapGrief.